- Published on

A Friendly Introduction to Zero Knowledge

Introduction

Zero Knowledge Proofs are magic. They allow us to do things we couldn't dream of before.

Let me start with a few quotes to tickle your brain. Some might be familiar, while others might be new to you.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

- Arthur C. Clarke

Civilization advances by extending the number of operations we can perform without thinking about them.

- Alfred North Whitehead

I have made this longer than usual, only because I have not had the time to make it shorter.

- Blaise Pascal

Privacy is the power to selectively reveal oneself to the world.

- A Cypherpunk's Manifesto

The future is already here. It's just not evenly distributed yet.

- William Gibson

Magic technology, advancing civilization, short letters, privacy, and a future that's already here. That's Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) in a nutshell. What's going on?

In the last century, computers and the Internet have taken over the world. These technologies are everywhere, in everything we do, for better or worse. On top of these, we build platforms, companies, empires. These are things like your MAMAA (Microsoft, Apple, Meta, Alphabet, Amazon). Then there's the belly of the beast - your payment networks, governmental services, and the plethora of B2B applications that silently run the world. Finally, there's a long tail of other things - your cute filter image app, language learning platform, or online community.

You expect to achieve a specific goal when you input data into yet another online service. It might be a small goal, like reaching out to a friend, distracting yourself from work, or something big like applying for a mortgage. But what happens to all this data? This includes the data you consciously know about and the iceberg of hidden data you are unaware of. Will what you are trying to achieve actually happen, or will there be some problem, either straight away or a year from now?

Who actually understands these systems and the consequences of how we use them? And how they, in turn, use us? While some people might understand some systems better than others, no one understands all of them, and even less how they interact together to create unforeseen consequences.

What's a human to do? Trust. But who do you trust? And why?

This is a hard problem. Our human brains have not evolved to think about this. The Internet, great as it is in connecting us and making things easier, has created a bit of a mess in this regard. In the past, when you had a private conversation with someone, the wind would blow away the sounds you made. When you were locked out of your house, you could get a locksmith, or break the lock yourself. Who do you talk to when you are locked out of your Google account and stare at an "Access denied" screen? No one, you are standing in front of an invisible and impenetrable castle.

ZKPs can help. Perhaps not for everything, everywhere, or at this precise moment. But it applies to numerous things, in various places, and increasingly so. In the rest of this article, I'll try to convince you why and how. Let's follow the magic.

What is a Zero Knowledge Proof?

This section introduces the notion of a Zero Knowledge Proof

This is the first in a series of posts on Zero Knowledge Proofs and their application. We'll look at what Zero Knowledge Proofs are, why you should care, how they work, and see where they can be used.

Imagine you go to a bar and can prove you are over 18 without revealing anything else, including your ID with personal information on it. Or you can prove that you've paid your taxes correctly, without revealing the details of your income or assets to anyone. These are the kind of things Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) enables. The term zero knowledge simply means we don't reveal any more information beyond what is intended.

ZKPs allow you to prove something without revealing anything but that the statement is true.

What does this mean? Let's take the classic example of "Where's Waldo". The game is about finding Waldo in a big picture. I can prove to you that I know where Waldo is without revealing the location of Waldo. How?

Imagine I have a picture of "Where's Waldo" and a large piece of paper four times the size of that picture. I make a small hole in the paper and put this paper in front of the "Where's Waldo" picture, carefully positioning it so that Waldo is visible through the hole. This means you can see Waldo, but only Waldo and nothing else. You thus know that I know where Waldo is, but I haven't revealed anything about where Waldo actually is located in the picture.

This is obviously a toy example, but hopefully it gives some intuition for how such a proof is even possible. But what does this mean? What are we proving more precisely? We'll dive deeper into this down the line, but for now let's see what ZKPs gives us more generally.

With ZKPs you can prove arbitrary statements in a general-purpose fashion. More specifically, ZKPs allow us to prove something in a private and succinct way.

This is extremely powerful as we'll see next.

Why should you care?

This section explains why someone might care about ZKPs, including going into detail on privacy, compression, and the general-purpose nature of ZKPs

Reading the above section you might think, "ok, that's kinda neat I guess, but why should I care". That's a completely reasonable take. In fact, you probably shouldn't! Just like you shouldn't care about how computers work, where AI is going, or any of these things.

Why might you care? Because you are curious and want to understand how ZKPs work, and what type of interactions it unlocks. The mechanism is very general, and the intuition for many people working in the space is that it is fundamentally a new paradigm that unlocks a lot of new things. We are seeing this already, and it seems like we are just at the very beginning of this. In the rest of this section, I'll give you some intuition as to why and how.

Before going deeper into that, let's understand what ZKPs give us at a higher level. ZKPs give us primarily one or both of the following properties:

- Privacy (more formally known as zero-knowledge)

- Compression (more formally known as succinctness)

What do we mean by these two notions? Here are some ways to think about these properties.

Privacy

There are a lot of things we want to keep private. Here's the definition of "private" in the Oxford Dictionary:

belonging to or for the use of one particular person or group of people only.

We have private conversations, private bathrooms, private parts. Business secrets, sensitive personal information, in the privacy of your own home. Keys, doors and locks.

Privacy is normal, and it is all around us. It is closely related to notions of self-sovereignty, self-determination, and independence. These notions come so naturally to us that many important documents, such as the US Bill of Rights and the United Nations Charter recognize them as fundamental rights for individuals and nations, respectively. 1 Privacy is a prerequisite for freedom.

More formally, the privacy property in ZKPs is often called zero knowledge or data hiding 2. A ZKP hides data that is irrelevant for some application to function, and this data is then bound together with the relevant application data. These notions are a bit more formal, and they enable privacy. Privacy is a broader and more generally applicable concept, so we'll keep focusing on that for now.

In the digital world, also known as cyberspace, as opposed to meatspace, privacy is essential too, but often neglected. Here's the definition of privacy given in A Cypherpunk's Manifesto:

Privacy is the power to selectively reveal oneself to the world.

- A Cypherpunk's Manifesto 3

Conversations, passwords, credit card information. These are examples of things we want to keep private online. The Internet is a fantastic tool that connects us all, but it is also an open and wild sea. There are a lot of strangers and predators, and keeping certain information private is vital. Without it, things like online shopping or private messaging would be impossible.

You might think, "We can already keep things like passwords private, what's the big deal?". In a limited sense, you are correct for these specific examples. We'll have to use more imagination to truly understand what general-purpose programmable privacy enables.

As an example, consider how Augustine, in his Confessions (400 AD) found the act of "silent reading" by St Ambrose, a bishop, out of the ordinary. At the time, most people would read out loud. 4

When [Ambrose] read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud.

Nowadays, everyone takes silent reading for granted. It is even hard to imagine that it had to be invented. The idea that what you read was something for your eyes only used to be foreign. What other similar inventions are possible in our modern era? Things that most of us are currently unable to imagine.

In future sections, we'll get a glimpse of what such inventions using ZKPs, both existing and upcoming, look like.

Compression

I have made this longer than usual, only because I have not had the time to make it shorter.

- Blaise Pascal 5

To compress something is defined as:

to press something into a smaller space

Similarly, succinctness is defined as:

the act of expressing something clearly in a few words

ZKPs having the property of compression means we can prove that something is true with a very short statement. For example, that all the steps in some computation have been executed correctly. This is most immediately useful when some resource is in high demand and expensive. This is true in the case of the Ethereum blockchain, but it is also a very useful property in other circumstances. What is more remarkable, is that the size of this proof stays the same regardless of how complex the thing we are trying to prove is!

What do we mean by "proof" and the "size of the proof"? These are mathematically precise notions that possess a great deal of nuance. In future sections, we'll go deeper into this notion of a proof in the context of ZKPs. For now, we can think of it as a short statement that we know is true, or can somehow verify is true.

In a typical whodunit like a Sherlock Holmes murder mystery, the detective gathers evidence until they can prove that the perpetrator has committed the murder. They then prove exactly how they know this in a grand finale. We can think of this final statement as the proof. 6

More formally, we call this property succinctness 7. This is what keeps the size of the proof the same regardless of what we are trying to prove. In the context of public blockchains, this also relates to the notion of scalability. For public blockchains like Ethereum, where block space is limited and expensive, ZKPs can make transactions a lot cheaper and faster. How? We create a proof that some set of transactions have taken place and put that tiny proof on-chain, as opposed to having all transactions take up space on the blockchain. With ZKPs, this can be made very secure.

Succinctness is a general property and orthogonal to "blockchains" - they just happen to be a good fit, for many reasons. More generally, having a short proof that something is true is very useful. There are a few ways to see why.

One way of looking at it is to consider transaction costs 8. Generally speaking, the lower these are, the more value and wealth is created. If there are fewer things to verify, or it is easier to do, then we can do things more freely and with ease.

Sometimes when we fill in a form we are asked to write our email twice to confirm it is correct. The idea is to protect against human errors and make the transmission of data more robust. There are also things like checksums, where an extra digit in your UPS package code, credit card number, or ISBN code for books acts as a simple check that all the numbers are probably correct. All of these are - obviously - not meant to protect against malicious use, but only against innocent mistakes. 9

In computer file systems, a hash is often used to ensure the integrity of files. If something happens to just a small part of a file, corrupting it, the hash changes completely. Because the hash is succinct (say, a 64 character string), it is easy to keep around and check even if the underlying file is huge. In this case, hash functions ensure integrity in a secure way. If we checked the integrity of a file by just keeping a copy of the file it'd be a lot more impractical. Big file, small file, it doesn't matter; the hash stays the same size. The succinctness of a hash enables this use case.

What do you know?

Let's take a step back from compression, succinctness, and proofs. We'll go on a little detour into knowledge, mental overhead, and trust. We'll then connect this back with ZKPs at the end of the section.

In your everyday life, what do you know is true, and why? If you see the sun rise every day, you likely expect it to rise again tomorrow. In the modern world, we are largely protected from the harsh environment in nature, but on the flip side, we have a lot of other, more modern, concerns. Many of these are related to various institutions we deal with on a daily basis.

If you are able to withdraw cash from your bank every day, do you expect to be able to withdraw it again the next day? Most people would probably say yes, but not everyone all the time. This depends on a lot of factors: if the bank is trustworthy, if you're living in a safe jurisdiction, if something major has happened in the world economy recently, what your personal circumstances are like etc. All of these things together make up some data points, and based on that you make a determination.

This is obviously a trivial example, but life is full of such interactions. All of this can be seen as a form of mental overhead. The extent to which this is a concern can depend on your personal situation and the complexity of your day-to-day dealings. For instance, a business might give these factors a lot more thought when entering into a contract with another party.

We create mechanisms and rules to counteract this uncertainty, such as using reputation services, independent auditing, imposing fines to discourage bad behavior, seeking accreditation by some trusted institutions, etc. All these measures are basically duct tape, trying to get to the crux of the matter. Is something what it claims to be? Does it follow the rules we have established? And is it trustworthy and usable?

All of this mental overhead gets compounded when you are dealing with multiple institutions, jurisdictions, companies, and people. You can get cascading effects, such as your bank failing and you being unable to pay your employees, thus leading to your business being unable to service its customers 10. More control measures are needed. More pauses to consider if things are right and what can go wrong.

I'll end this section with a quote:

Civilization advances by extending the number of operations we can perform without thinking about them.

- Alfred North Whitehead 11

For example, when you light the stove to make dinner, you don't even have to think about making a fire. This is very different from having to gather wood, keep it dry, create a fire, and keep it going, a very time-consuming process. In mathematics, without calculus, we wouldn't be able to go to the moon.

With ZKPs and succinct proofs, we are able to introduce more certainty and clarity into opaque systems. This gets even more powerful when we consider composing ZKPs. That is combining multiple proofs into one in some fashion, such as with aggregation or recursion.

All of this presumes we can translate some of the mechanisms or rules mentioned above - which are often messy and inconsistent - into a form that ZKPs can comprehend. How can we do that?

General-purpose

Recall that ZKPs allow us to prove arbitrary statements in a general-purpose fashion. Why does this matter and how is this powerful?

The difference between similar existing tools and ZKPs is like the difference between a calculator and a computer. One is meant for a very specific task, and the other is general-purpose. It is the difference between this calculating machine 12 and a modern computer:

Recall the specific examples we gave above to represent privacy and succinctness more concretely. A password is a private piece of information that allows you to log in to some service 13. In the case of a hash of some input data, such as a file, it gives us something succinct to check equality to.

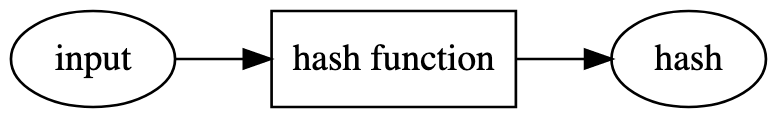

We can visualize a hash function as follows:

We apply a specific hash function, such as SHA256 14, on some known input data. For example, using the sentence "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" (without quotation marks) as input and applying the SHA256 hash function results in the hash d7a8fbb307d7809469ca9abcb0082e4f8d5651e46d3cdb762d02d0bf37c9e592. Adding a "." at the end of the sentence gives a completely different hash value: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog." hashes to ef537f25c895bfa782526529a9b63d97aa631564d5d789c2b765448c8635fb6c.

Even though the sentence just changed a tiny bit, the resulting hashes are very different 15. Hash functions that are secure are hard to "break" and have some nice properties. For example, if you have the hash value, you can't recreate the initial input. You also can't easily construct a message that hashes to a specific, predetermined hash value. These hash functions are called cryptographic hash functions. 16

The SHA256 hash function we used above is a specific cryptographic hash function that took a lot of time and many people to make secure. The hash itself also doesn't prove anything. It only makes sense when compared with something else, such as having direct access to the message or file.

Informally, we can think of a hash function as providing a proof that some specific message corresponds to a particular hash. We can only verify this with the original message. Sometimes people use this to prove they wrote something and make predictions - they write "On April 1, 2040, aliens will land on top of Big Ben in London, and the lottery number 25742069 will win a jackpot." and then post the hash of this message publicly ahead of time, say on Twitter. When it turns out they are right, they can reveal the original message, and people can be convinced that they did predict the future and are the next Nostradamus.

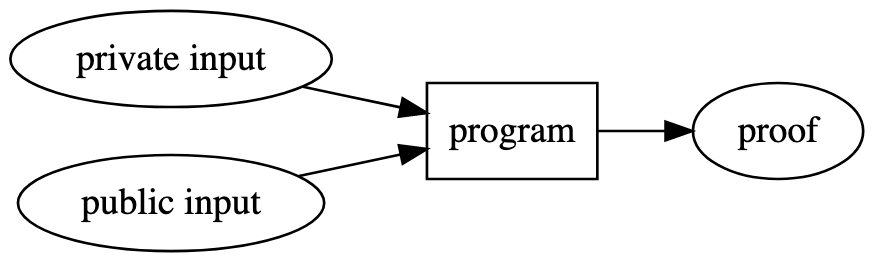

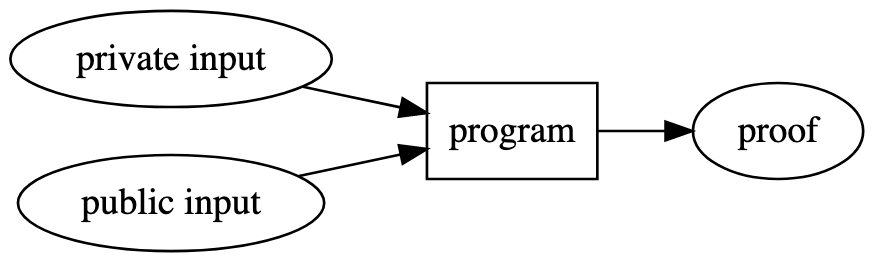

In contrast, we can visualize a ZKP as follows:

Unlike in the hash function above, there are a few big differences:

- We have multiple private and public inputs as opposed to only a single (public) input

- We can use any program, not just a cryptographic hash function

- We produce a self-contained proof that can be verified

In the hash function example above, we need to make the input public in order to verify that the message corresponds to the hash. For ZKPs, we can also have private input. Private input is something that only you can see. That is, you don't need to reveal it to anyone in order to produce a proof.

For example, in the "Where's Waldo" case at the beginning of this article, the public input would be the picture of Where's Waldo. The private input is the actual location of Waldo. I can produce a proof that I know where Waldo is without revealing the private input, the location of Waldo, to you.

Similarly, if I have a Sudoku puzzle (a popular logic puzzle), I can prove to you that I know a solution to the puzzle without revealing the solution to you. In this case, the public input is the initial puzzle, and the private input is the solution to the puzzle.

You might have noticed that Where's Waldo and solving a Sudoku puzzle are two very different problems. Yet we can write a simple program that expresses how either of these works and uses ZKP to create a proof. That is because the logic inside this special program is general-purpose and can compute anything a computer can.

We have turned what was originally a problem of cryptography or math - defining and making a cryptographic hash function secure - into one of programming. To see why this is extremely powerful, consider some of the following examples.

We can now prove that we know the private data that results in a certain hash 17. This means you can prove that you are in possession of a certain message, such as an important document, without revealing the message itself.

To better understand the power of doing general-purpose computing, let's take a closer look at group signature. Group signatures are a way for a group of individuals to sign a document together, without revealing who they are. For example, the Federalist Papers were signed by the pseudonym Publius which represented multiple individuals 18. Just like in the case of the SHA256 hash function, there's a way to express group signatures with cryptography and math. This is very impressive and took a lot of cryptographic engineering to develop. But with general-purpose ZKPs anyone can express the same thing in just a few dozen lines of Circom, a programming language for ZKPs, code 19.

Due to its general nature, we can easily make ad hoc constructions. For example, you might have an ID card that has your full name, address, and other personal information. To enter an event, you might need to be over 18 and have a valid ticket. You might not want a random person or online system to see your address or risk having your ID stolen. With ZKPs you can prove that:

- You possess a valid ID

- The ID has been issued by an approved institution in the last 5 years

- The ID has not been revoked or reported stolen recently

- You are over 18 years of age

- You have paid for a valid ticket to the event

- The ticket has not been used before

All without revealing any single fact about yourself other than what is listed above.

With ZKPs, we now have a better tool for people to coordinate in various ways, especially when it comes to systems where you want privacy and succinctness. We'll see even more examples in the application section.

Often, it is your imagination that is the limit in terms of what you can express.

Why now?

Why are ZKPs becoming a thing now? There are both technical and social reasons for this.

Technically, ZKPs are fairly new. Mathematically they've only existed for a few decades 20. Similar to computing itself, it then took a while to become performant and practical, even in theory. 21

After that, someone had to take these papers and cryptographic protocols and turn them into something practical. The first notable example of this was Zcash, the privacy-preserving cryptocurrency, in 2016. It started as a paper written by cypherpunks and researchers 22. The first version was an impressive feat of research and engineering applied to an end product and system. While the system had many issues and was far from optimal, it was the first real practical example of using ZKPs in the real world. This showed people that it was possible and practical to use ZKPs in the real world. This has led to an explosion of research and engineering efforts in ZKP, especially in recent years.

Public blockchains like Ethereum and Zcash, a privacy-preserving cryptocurrency, had a big role to play in this. What blockchains excel at are things like censorship resistance and transparency 23. This comes at the cost of a lack of privacy and scalability, something that ZKPs excel at. In this sense, they are a natural fit. Couple that with the blockchain community's appetite for advanced cryptography 24, and it is no wonder a lot of the innovation is happening at the intersection between blockchain and ZKPs 25. Due to the many well-capitalized blockchain projects, this has also led to more investment into research and engineering in a traditionally more academic space.

Considering the complexity involved, spanning applied mathematics, cryptography, papers on specific ZKP systems, implementing novel proof systems, tooling, and applications that touch other complex domains, things are moving extremely fast. Every year - even every month - there are new research papers with novel techniques, improved tooling, and applications. The feedback loop between new research and it being implemented and then used is getting tighter. While still difficult, it is getting easier and easier to get started. As tooling is improved, developers need to understand the math behind ZKPs less and less.

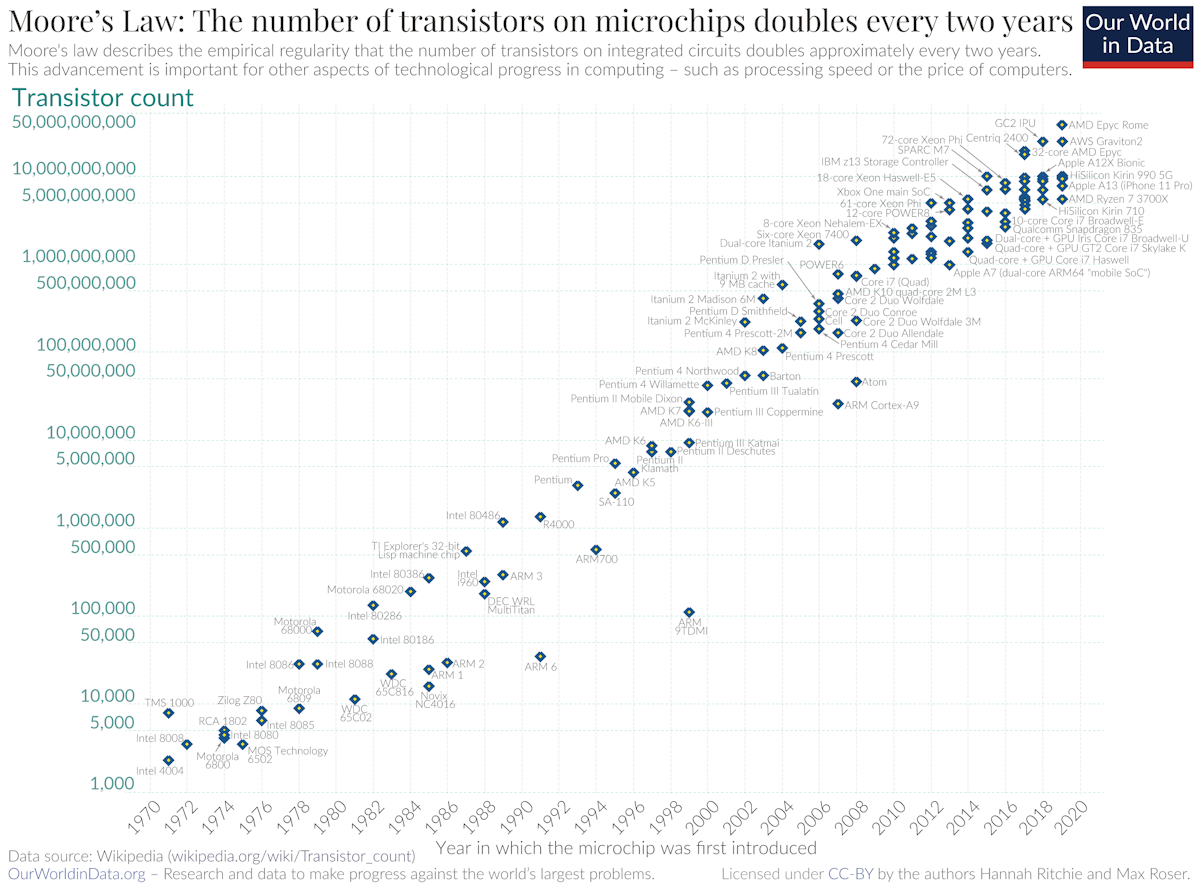

In terms of the performance of ZKPs, there's a form of Moore's law happening. Moore's law is the observation that the number of transistors doubles about every two years. This is what led to the computer revolution. In ZKPs, projects that were just pipe dreams a few years ago, seen as completely unpractical, are now being executed on, things like zkVM and zkML. As a rule of thumb, it has been observed in the ZKP world that things improve by an order of magnitude every other year or so 26. This is because it is a new technology, and it is possible to aggressively optimize on many layers of the stack, from the programs we write, to the systems we use, to the hardware itself. We have no reason to believe this will stop any time soon.

How does it work?

This section explains how Zero Knowledge Proofs work at a high level

This section provides a high-level overview of how ZKPs work. It will not include any mathematics or code.

Basics

We start by introducing some terminology. There'll be a few new terms to learn, but as we go along, you'll get the hang of it.

- Protocol: system of rules that explain the correct conduct to be followed

- Proof: argument establishing the truth of a statement

- Prover: someone who proves or demonstrates something

- Verifier: someone who vouches for the correctness of a statement

- Private input: Input that only the prover can see, often called witness

- Public input: Input that both prover and verifier can see, often called instance

While it is useful to learn the terminology used in the field, some metaphors can be helpful in getting a better sense of what's going on. We'll introduce more terms as we go.

Protocols exist everywhere and can be implicit or explicit. In the game of chess, the protocol is that you have two players who take turns to play a move according to the rules of the game until the game ends, and one person wins, or there is a draw. In theory, the time it takes to make a move doesn't matter, but in practice, we try to minimize the communication costs between the two parties interacting. We can thus think of it as a really fast game of chess.

We can think of Sherlock Holmes as the prover, and in his final statement he produces an elegant series of arguments, a proof, that someone is the murderer. This must then be verified by a verifier to be true, for example by a judge or jury, beyond a reasonable doubt 27. The 'prover' refers to an entity, here Holmes, producing the proof, which must then be verified. Because the proof is self-contained, anyone can be a verifier, including you as the reader, who must be convinced of the reasoning provided to make the story believable. 28

The private input would be some knowledge that only Sherlock Holmes knows, for example some secret information someone whispered in his ears. This is often confusingly called witness, presumably because a witness in a courtroom has some private information, and this is added to the pile of evidence. In the case of ZKPs, this private information would not be shared with the verifier, or judge and jury in this example.

ZKPs establish a protocol between a prover and a verifier. This protocol is non-interactive if the prover and verifier don't have to interact or communicate directly, like in a game of chess or in a dance. Instead, the prover produces a single self-contained proof, and at some later point, this gets verified. Most ZKPs start off as interactive - that is, requiring multiple back and forths - and we then use some mathematical tricks to make it non-interactive 29. You can think of non-interactivity kind of as two chess players who, after uttering a few words, know every single move the other player will play, so they don't even start the game because they already know how it will end.

There are many types of ZKPs. We often talk about zk-SNARKs, which stands for Zero Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive ARguments of Knowledge. Zero Knowledge and Succinctness correspond to privacy and compression above, respectively. Non-interactive was mentioned. "ARguments of knowledge" is basically the same thing as a proof 30. There are many different types of zk-SNARKs too.

A good mental model is to think of ZKPs as a zoo. There are a lot of animals there, and we can categorize them in various ways: these animals have four legs, these have stripes, Bob brought these in last year 31, etc. Some categories are more useful than others. In fact, some of these systems don't even have Zero Knowledge! These are usually called just SNARKs. As a community, we often call this zoo of different animals ZK, even if there are many systems that don't actually use the Zero Knowledge property. 32

Protocol

Going back to our protocol, we have a prover and verifier. The prover creates a proof using a prover key, private input and public input. The verifier verifies the proof using a verification key and public input, and outputs true or false.

We have two new things, a prover key and a verifier key. This is what allows the prover and verifier to do their magic. You can think of them as a regular key that allows you to enter somewhere and do something, or you can think of them as a magic wand that allows you to do something. We get these keys from a special ceremony called a setup, which is an initial preparation phase that we won't go into detail about in this article 33.

Notice that only the prover has access to the private input. How does the prover use the prover key, private input and public input to turn it into a proof?

Recall the illustration of a ZKP from before:

We have a special program (formally known as a circuit) that encodes the logic a user cares about. For example, proving that they know the data that results in a certain hash value. Unlike a normal computer program, this program is made up of constraints 34. We are proving that all the constraints hold together with the private and public input.

Finally, the verifier takes this short proof, combines it with the verification key, public input and the special program with all the constraints and convinces itself beyond a reasonable doubt that the proof is correct and outputs "true". If it isn't correct it'll output "false".

This is a somewhat simplified view but it captures the essence of what is going on.

Constraints

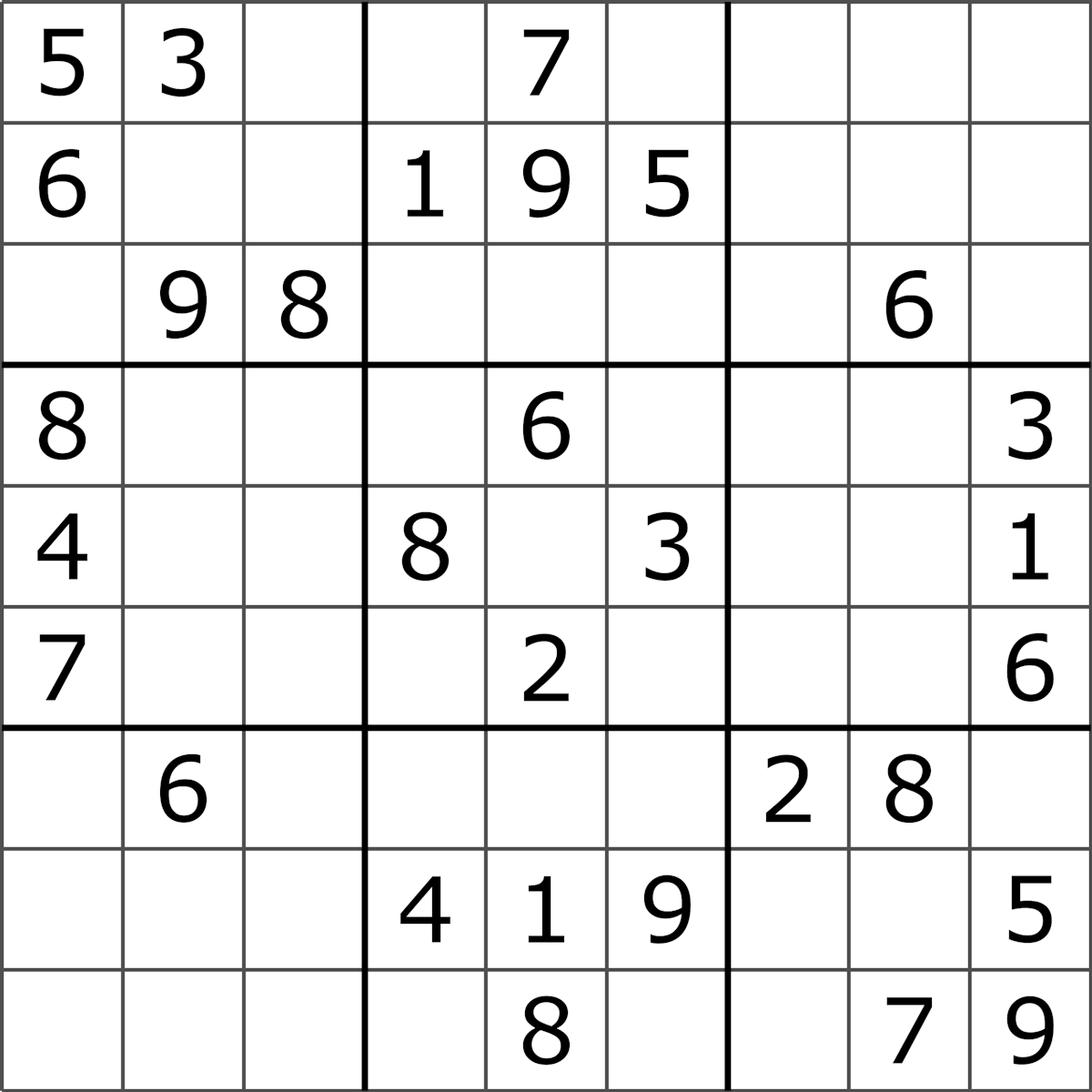

What are these constraints that make up the special program above? A constraint is a limitation or restriction. For example, "a number between 1 and 9" is a constraint. The number 7 satisfies this constraint, and the number 11 doesn't. How do we write a program as a set of constraints? This is an art on its own, but let's start by looking at a simple example: Sudoku.

In the game of Sudoku the goal is to find a solution to a board that satisfies some constraints. Each row should include the numbers 1 to 9 but only once. The same goes for each column and each 3x3 subsquare. We are given some initial starting position, and then our job is to fill in the rest in a way that satisfies all these constraints. The tricky part is finding numbers that satisfy all the constraints at once.

With ZKPs, a prover can construct a proof that they know the solution to a certain puzzle. In this case, the proving consists of using some public input, the initial board position, and some private input, their solution to the puzzle, and a circuit. The circuit consists of all the constraints that express the puzzle.

It is called a circuit because these constraints are related to each other, and we wire these constraints together, kind of like an electric circuit. In this case the circuit isn't dealing with current, but with values. For example, we can't stick any value like "banana" in our row constraint, it has to be a number, and the number has to be between 1 and 9, and so on.

The verifier has the same circuit and public input, and can verify the proof the prover sent them. Assuming the proof is valid, the verifier is convinced that the prover has a solution to that specific puzzle.

It turns out that a lot of problems can be expressed as a set of constraints. In fact, any problem we can solve with a computer can be expressed as a set of constraints.

Sudoku example

Let's apply what we learned about the various parts of a ZKP to the Sudoku example above.

For Sudoku, our special program, the circuit, takes two inputs:

- A Sudoku puzzle as public input

- A solution to a Sudoku puzzle as private input

The circuit is made up of a set of constraints. All of these constraints have to be true. The constraints look like this:

- All digits in the puzzle and solution have to be between 1 and 9

- The solution has to be equal to the puzzle in all the places where digits are already placed

- All rows must contain digits 1 through 9 exactly once

- All columns must contain digits 1 through 9 exactly once

- All subsquares must contain digits 1 through 9 exactly once

If all of these constraints are true for a puzzle and its solution, we know that it is a valid solution.

A prover Peggy uses her magic prover key, the puzzle and the solution, combines it with the special program and creates a proof. The proof is very short, less than 1000 characters. The proof is self-contained and with it the verifier has all information they need to verify the proof. You can think of it as a magic spell that does what you want, without you having to understand the details of it 35.

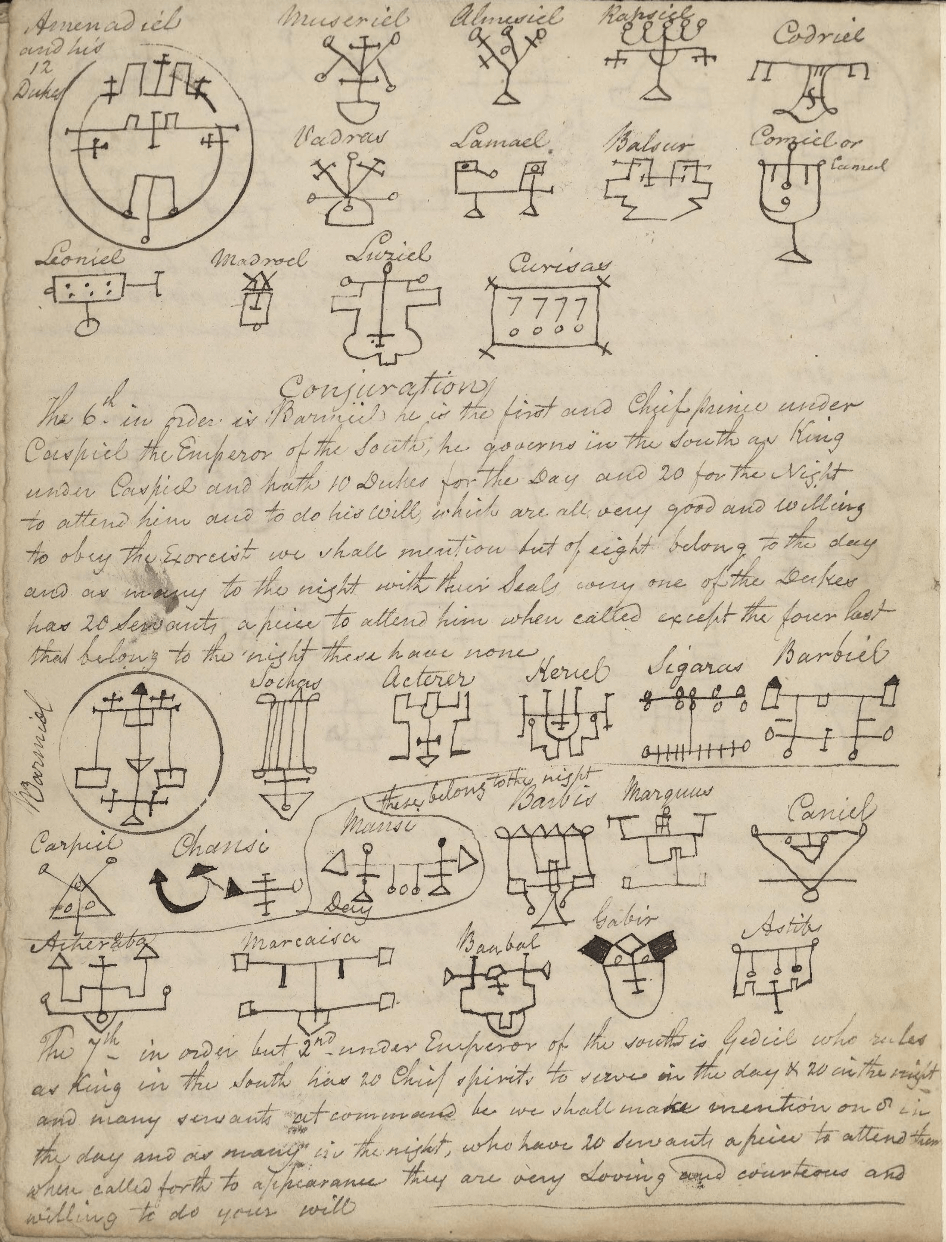

Here's a spell from a book of magic spells, written by a Welsh physician in the 19th century:

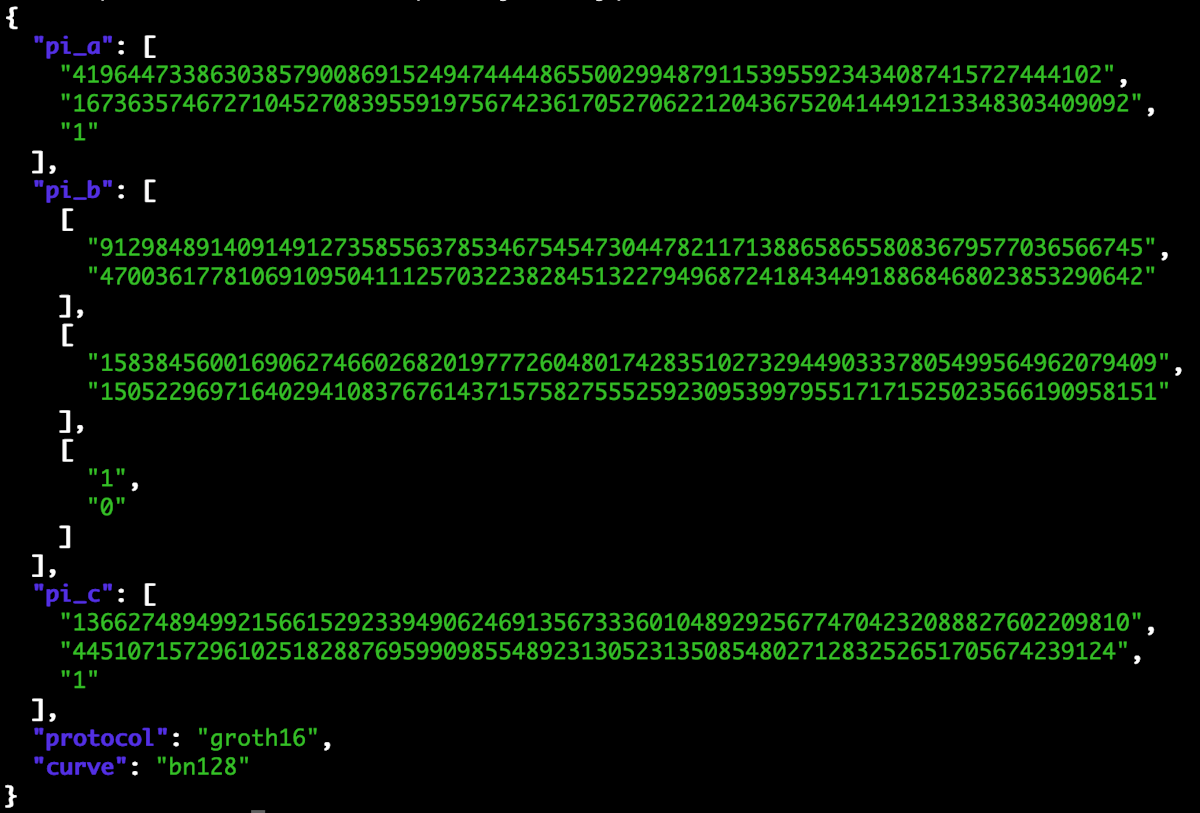

Here's an example of a Zero Knowledge Proof produced by the Circom/snarkjs library:

Except in this case, the magic actually works.

Victor the verifier uses his verifier key, the original puzzle input, and verifies that the proof Peggy sent is indeed correct. If it is, the output is "true", and if it isn't, the output is "false". The spell either works or it doesn't. With this, Victor is convinced that Peggy knows a solution to that specific puzzle, without actually having seen the solution. Et voilà. 36

Some properties

We say that a ZKP has certain technical properties:

- Completeness - if the statement is true, then the verifier will be convinced by the proof

- Soundness - if the statement is false, the verifier won't be convinced by the proof, except with a negligible probability

- Zero Knowledge - if the statement is true, it won't reveal anything but the fact that it is true

Additionally, for zk-SNARKs, the proof is succinct, meaning it basically doesn't get bigger as the program gets more complex 37.

There are many other properties we care about when it comes to practical ZKPs:

- What mathematical assumptions is the system making?

- How secure is it?

- Does it require a trusted setup?

- How hard is it to generate the proof? In time and other resources

- How hard is it to verify the proof? In time and other resources

- Does the ZKP system allow for aggregating and combining multiple proofs together?

- Are there any good libraries for a ZKP system that can be used by programmers?

- How expressive is the language used to write programs for a particular ZKP system?

- And so on

As you can see, there are quite a lot of considerations and different variations of ZKPs. Don't worry though, the gist is basically the same, and depending on where your interest lies you can remain blissfully unaware of many of the technical details involved. Going back to the zoo metaphor, just like with animals, you might not want to become a biologist. Instead, you might want to work with some animals, or maybe you just want a pet, or even just pet your friend's dog.

Applications

This section gives examples of current and future applications of ZK

There are many applications of ZKPs. Generally speaking, we are still in the early stages. A lot of the focus is still on the underlying protocols and infrastructure, as well as blockchain-specific applications. To better appreciate the blockchain-specific examples, it is useful to have some understanding of how public blockchains work and the challenges they have. However, this isn't a requirement. In this section we'll look at some of the more interesting applications. We'll start by looking at applications that are live now and then look at those on the horizon.

The future is already here. It's just not evenly distributed yet.

- William Gibson 38

Live now

Electronic cash. To make a cash-like payments systems online it needs to be fungible and private like physical cash. Fungibility refers to the property of a commodity being replaceable by another identical item. That is, there's no difference between your money and my money; they are equally valid forms of payment. We can use ZK to make the transaction graph private, unlike in Bitcoin or Ethereum. This way, your transaction history remains private, ensuring that electronic cash is fungible. This is currently live in systems like Zcash, and related systems like Tornado Cash 39.

Anonymous signaling. Often, we might need to prove our affiliation with a group that possesses certain characteristics, without revealing our identities. One such example is proving that you are part of some group of people; another is voting. This means you don't tie your identity to sensitive actions such as which party you voted for, or reveal other unnecessary information. Currently live in systems like Semaphore 40, and similar mechanisms with many variations exist.

ZK Rollup. Allow for more, cheaper and faster transactions. The Ethereum blockchain space is limited and expensive with a lot of demand. We use a so-called Layer 2 (L2) rollup, that does transactions separate from the main blockchain (L1). Once a certain number of transactions have hit the L2, it "rolls it up" to the L1. ZKPs are great for this because we can (i) prove that transactions are executed correctly and (ii) create a succinct proof that takes up a small amount of space on the L1. This makes transactions cheaper and faster for users, with near-equal security. Due to the complexity of proving the execution of the entire Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) many ZK Rollup solutions only focus on the exchange of simple commodities and assets. Currently live in systems like Loopring, zkSync Lite, dYdX, and Starknet. 41

ZK-EVM. Similar to ZK Rollup, but universal, since any type of transaction or program can be executed. Ethereum has an EVM that acts as a worldwide globally shared, general purpose computer (that anyone can write to). By writing the logic of this machine using ZKPs we can prove the correct execution of any program written on Ethereum and construct a succinct proof that it was executed correctly. This has several use cases, but most immediately for scaling and allowing for cheaper and faster transactions. Currently live in systems like Polygon zkEVM, zkSync Era, with several others on their way. 42

ZK-VM. Partially due to the complexity of targeting a "snark-unfriendly" 43 platform like the EVM, many projects have chosen to do a new blockchain, separate from Ethereum. This means they can optimize the VM to work better with ZK in the first place. Depending on the specific system, this allows for privacy and succinct verification of the blockchain state. Mina is live, and systems like Aleo are under active development. 44

Dark Forest. Dark Forest is an incomplete information real-time-strategy game. Incomplete information games based on ZK have a "cryptographic fog of war" where players can only see part of the world, as enforced by ZK. Compared to traditional games like Starcraft, not even a central server has access to all the information. Due to its programmatic nature this enables novel ways of playing a game. 45

ZK Bridges. Bridges allow you to move assets between different blockchains and systems. These bridges can be hard to make secure, and they often get hacked. With ZK, we can bridge assets more securely and faster, without relying on trusted third parties or error-prone approaches. Currently live with zkBridge and also being worked on by projects such as Succinct Labs. 46

Private identity. As more siloed systems require and host our online identities 47, it is desirable for individuals to be able to own, aggregate and keep these fragmented online identities private. Currently live projects like Sismo enable this, and other projects are working on similar systems. 48

These are just a few examples and by no means complete. We didn't talk about things like private non-repudiable reputation, exporting web2 reputation, sybil-resistant denial-of-service protection, coercion-resistant proving, proof of replication, anonymous airdrops, proving degrees of separation, etc. 49

On the horizon

ZK-EVM (Ethereum-equivalence). There are different types of ZK-EVM, and the more challenging ones to implement are the ones that are fully Ethereum-equivalent. Other ZK-EVM takes some shortcuts to make it easier to generate proofs. With a fully Ethereum-equivalent ZK-EVM there's no difference with the current Ethereum system. This means we can prove the correct execution of every single block in existence in a succinct proof. You can use a phone to verify the integrity of the entire chain, relying solely on mathematics, without needing to trust third parties or use expensive machines. Currently being worked on by the ZK-EVM Community Edition team. 50

General purpose provable computation. Most computation in the world doesn't happen in the EVM, but in other systems. WASM and LLVM-based programs are very common 51. We can leverage the same approach in ZK-EVM to do general-purpose private provable computation. For example, we can prove that a database contains a specific record, without revealing any other information. Currently being worked on by many different teams, for example Delphinus Labs, RISC Zero, Orochi Network, and nil.foundation. 52

ZK Machine Learning (ZK ML). We can prove that some computation was done correctly privately, off-chain, and then publish a proof that the computation was done correctly. This means we can use private data for training better models, without revealing that data. For example, sensitive documents, voice or even things like DNA to find health problems. This improves both scalability and privacy for users. Current proof of concept (PoC) exists for things like MNIST, a common test used in Machine Learning to recognize handwritten digits, and people are working on more complex things like neural networks inside ZKPs. 53

Photo authenticity. Prove provenance of content such as photos and videos, including standard post-processing edits. That is, prove that a photo was taken at a certain time and place, and has only been edited with basic resizing, cropping, and use of greyscale (AP approved list of operations). Some work has been done, including a PoC. 54

Compliance. Prove that a private transaction is compliant with some regulation, or that an asset isn't on a specific blacklist. Prove that an exchange is solvent without revealing its assets. Some work has been done by systems such as Espresso Labs, and some systems have simple versions of this already.

Shielded and private intents. Users of public blockchains have specific goals they want to achieve, which can be expressed as intents. For example, a user might have the intent to exchange one token for another. A user can tell other users about their intents and be matched with a suitable counterparty. It is desirable to keep these intents shielded (hiding the "who" but not the "what", similar to shielded transactions in Zcash) or completely private. Currently worked on by Anoma, starting with shielded intent-matching. To make intents-matching fully private likely requires breakthrough advances in cryptography, similar to the last example in this section.

Autonomous worlds. A continuation of things like Dark Forest. A world can be physical or conceptual, like The World of Narnina, Christianity, The World of the US Dollar, Bitcoin or Commonwealth law. Depending on where these worlds run, these can be autonomous if anyone can change the rules without damaging its objectivity. Currently being explored by the 0xPARC Foundation in the context of games and creating these worlds. 55

Proof of data authenticity. Export data from web applications and prove facts about it in a private way. Uses the TLS protocol which means it works on any modern website. Currently being worked on by TLSNotary. 56

Nuclear disarmament. Allow people inspecting nuclear sites to confirm that an object is or isn't a nuclear weapon without inspecting any of the sensitive internal workings of said object. Paper with physical simulation work exists. 57

Peace talks and high-stakes negotiation. Often in negotiations people have certain hard limits that they do not wish to reveal to their counterparty to weaken their ability to negotiate. By explicitly encoding these, two parties can negotiate over some highly complex domain and reach an agreement without revealing the details of their precise parameters and limits. This allows people who do not trust each other to fruitfully come to some agreement. Likely requires some breakthroughs in Multi-Party Computation (MPC), which allows us to do computation on shared secrets. 58

Again, this didn't mention all the types of things people are working on or thinking about. There will surely be many more things in the future. As you can tell there are a lot of things we can do with ZK.

You might wonder why many of these applications involve a blockchain. This was partially answered in the previous section "Why now?". ZK is an orthogonal technology to blockchains like Ethereum and we can do without the blockchain, but quite often it is simply a good tool that makes sense to leverage.

Similarly, the group of people working on these things and the immediate problems they care about are often overlapping. As the space matures, we can expect the "blockchain" part of ZK applications to disappear as simply an implementation detail, and this has already happened to some degree. Looking further, the "ZK" part will likely also fall into the background and it'll simply be an application that happens to use ZKP.

Finally, when cryptography for online messaging and similar was developed, it was used and developed by the military and Internet companies. It was not something that was innovated on by the post office or some company involved in the secure transport of physical goods, even if in theory that was a possibility. 59.

I'll end this section with a quote from Barry Whitehat, a well-known ZK researcher who works with the Privacy and Scalability Explorations (PSE) team at the Ethereum Foundation, when asked for predictions on the future of ZK:

"By 2040, someone will have won a Nobel Peace Prize for using Zero Knowledge Proofs." 60

Outlandish and bold? Certainly. Will it turn out to be true? Maybe not. But could it? Absolutely. It is an intriguing prospect to consider. What is the difference between the mental model that sees this as a real possibility, versus one that writes it off immediately? What would have to happen for such an event to be a realistic outcome?

ZKPs represent a new and incredibly potent tool. Often, it's our imagination about its potential applications that limits us.

Conclusion

This section summarizes the article and provides next steps

In this article, we've looked at what ZKPs are, why we should care about them and when they are useful. We've also looked at how they work and what properties they give us. Finally, we looked at some applications, both current and future ones.

I hope this has led you to better understand the nature of ZKPs, and perhaps led to some aha moments and inspired some new ways of thinking about things. Perhaps it even helps you follow the magic of ZKPs in the future.

In future posts, we'll go even deeper into some of these aspects, and we'll also look at more technical aspects to better understand how ZKPs work and where they can be used.

If something specific piqued your interest, or there is something specific you'd like to see in future articles, feel free to contact me on Twitter or by email. I'll include the best comments as footnotes!

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Michelle Lai, Chih-Cheng Liang, Jenny Lin, Anna Lindegren and Eve Ko for reading drafts and providing feedback on this.

Images

- Where's Waldo - Unknown source, Where's Waldo originally created by Martin Handford

- Silent Reading - Jorge Royan, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Sherlock Holmes - Sidney Paget, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Moon landing - Neil A. Armstrong, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Pascal's Calculator - kitmasterbloke, CC-BY 2.0, via Openverse

- Moore's law - Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, CC-BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Sudoku puzzle - Tim Stellmach, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Magic spell - National Library of Wales, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Cyberpunk - bloodlessbaron, Public Domain, via Openverse

References

Footnotes

-

While the concepts are related, there's some legal controversy around if the "the right to privacy" itself is protected in many jurisdictions around the world. See the Wikipedia article on Right to privacy for more. ↩

-

Zero knowledge has a precise mathematical definition, but we won't go into this in this article. See ZKProof Community Reference for a more precise definition. ↩

-

See A Cypherpunk Manifesto for the full text. Also see Wikipedia on Cypherpunks. ↩

-

Some people have different interpretations of this specific passage, but it is still the case that humans made the transition from primarily oral storytelling to silent reading at some point not too long ago. See Wikipedia on History of silent reading for more on silent reading. ↩

-

Original quote in French: Je n'ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n'ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte. See Quote Investigator on this quote. ↩

-

Kudos to Juraj Bednar for suggesting using murder mystery as a way to explain the notion of a proof. ↩

-

Succinctness has a precise mathematical definition, but we won't go into this in this article. See ZKProof Community Reference for a more precise definition. ↩

-

Transaction costs is an economic concept. See this Wikipedia article on transaction costs. ↩

-

In a checksum, we do some basic operations like adding and subtracting the initial digits, and if the final digit isn't the same we know something went wrong. Fun fact: Unlike most similar ID systems, a Social Security Number (SSN) in the US does not have a checksum. If a checksum is just one digit long it is sometimes just called a check digit. ↩

-

While more common in less developed countries, this happened recently with bank failures in the US. See Wikipedia article on effects of Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. ↩

-

Full quote: "It is a profoundly erroneous truism, repeated by all copy-books and by eminent people when they are making speeches, that we should cultivate the habit of thinking of what we are doing. The precise opposite is the case. Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them. Operations of thought are like cavalry charges in a battle — they are strictly limited in number, they require fresh horses, and must only be made at decisive moments." See Wikiquote. ↩

-

Pascal's calculator, the Pascaline, is a mechanical calculator. It was very impressive when it came out in 1642. See Pascal's calculator. ↩

-

In well-designed authentication schemes the provider doesn't see your password either, just a salted hash of it. See Wikipedia on form of stored passwords. ↩

-

SHA256 is a an often used cryptographic hash function. See SHA2. ↩

-

You can verify this yourself with a SHA256 calculator online or do it yourself at your computer with the

sha256sumutility. ↩ -

Cryptography studies how to keep information safe and hide it from adversaries. It is a blend of mathematics, computer science and engineering. You can also read more about cryptographic hash functions and their purpose here. ↩

-

Technically this is called proving knowledge of the pre-image of a hash. ↩

-

See the Federalist Papers. ↩

-

See this article on group signatures by 0xPARC. Includes the relevant Circom code. ↩

-

Zero Knowledge Proofs have existed since 1985, and the authors later won a Gödel Prize for their work. We can compare this to public-key cryptography, which took many decades until it was used for things like TLS, a now indispensable building block for secure Internet usage. ↩

-

For example, Lambda calculus with Church numerals and Lisp were initially theoretical and largely unpractical when first proposed. Dan Boneh and others have made the observation that making prover time quasilinear is what really made ZKPs practical, even in theory. ↩

-

See the origins of Zcash, the Zerocoin paper. ↩

-

Censorship-resistance means anyone can transact on a public blockchain without permission as long as they follow the basic rules of the protocol. It also means it is very costly for an attacker to alter or disrupt the operation of the system. Transparency refers to transactions being publicly auditable and immutable on the blockchain forever. These notions are closely related to decentralization and security, and are a big part of the value proposition of public blockchains compared to other systems. ↩

-

BLS signatures used in the Ethereum Consensus Layer were deployed and used to secure billions of dollars just a few years after it was developed. See Wikipedia for more on BLS Signatures. ↩

-

Dan Boneh, an applied cryptography professor at Stanford, is a great example of this in terms of his involvement in various cryptocurrency-related projects. ↩

-

Thee author heard about this from gubsheep at 0xPARC, but it has popped up a few times. This also matches the author's own experience, working on RLN and noticing 1-2 order of magnitude improvements in things like prover time in a few years. ↩

-

In a legal setting, false positives do happen, see for example the Innocence Project. In a mathematical setting we can make this false positive rate very precise, and it isn't even close to a fair game. That's the power of mathematics. We'll look at this more in future articles on probabilistic proofs. ↩

-

You'd probably want to ask Sherlock Holmes some follow-up questions first though, before throwing our prospective murderer in jail. It is possible Sherlock Holmes is trying to fool you! In ZKPs we assume the prover is untrusted. ↩

-

This is done using the Fiat-Shamir heuristic. ↩

-

Sometimes people make a distinction between these two, but it is a technical one (computational vs statistical soundness) and not something we have to concern ourselves with right now. See ZKProof Community Reference for more. ↩

-

Alice and Bob are commonly used characters in cryptographic systems, see Wikipedia. ↩

-

There are also zk-STARKs, so one could argue a more accurate name might be (zk)S(T|N)ARKs. This is obviously a bit of a mouthful, so people tend to use ZK as a shorthand. See for example the name of the ZK podcast, the ZK proof standard, etc. ZK is the most magical property of ZKPs, in the author's opinion. ↩

-

Setups are multi-faceted and a big part of the security assumptions of a ZKP. They are a bit involved mathematically, and to give them full justice would need a dedicated article. There's a great layman's podcast on The Ceremony Zcash held in 2016 that you can listen to here. ↩

-

Technically speaking this is an arithmetic circuit (dealing with numbers), but we won't introduce details of this in this article. See ZKProof Community Reference for more. ↩

-

Unless you want to! ZK is sometimes called "Magic Moon Math", but if you really study it the mathematics you need to get an intuition for how they actually work under the hood isn't as complex as you might think. We won't go into it in this article, though. Here's a presentation by the author on some of the mathematical foundations of ZKPs. ↩

-

French for here you go, presto, bingo, ta-da, and Bob's your uncle. ↩

-

There are different notions of succinctness, and this depends on the specific proof system. Technically, we call proofs succinct if they are sublinear in time complexity. ↩

-

With many new versions being developed, like Aztec and Railgun. Tornado Cash (archive) works quite differently from Zcash, acting more as a mixer. Tornado Cash was also recently sanctioned by the US government. As of this writing there are still a lot of unknowns about this case, but it was a controversial event that lead to lawsuits. Some see this as a sequel to the Crypto Wars in the 1990s. There are other alternatives like Monero and Wasabi Wallet, that are not based on ZKP but have similar design goals. Read more about the Case for Electronic Cash by Coin Center. ↩

-

See Semaphore by the Privacy & Scaling Explorations team. ↩

-

This is similar to how the traditional banking system works too, where there are multiple layers of settlement happening. It is just hidden from most end users. See L2Beat for an overview of different Layer 2 solutions, including ZK Rollups. Also see Loopring, dYdX. and Starknet. ↩

-

There are different types of zkEVM, and the difference can be quite subtle. See this post by Vitalik for more on the difference. Also see Polygon zkEVM, zkSync Era. ↩

-

SNARK-unfriendly platforms or functions refer to the fact that most modern computer primitives were designed for a specific computer architecture. This architecture is very different from what is natural when writing constraints. For example, the SHA256 hash function is a typical example of a SNARK-unfriendly hash. Some people create SNARK or ZK-friendly functions, such as the Poseidon hash function, that are designed specifically to be used in ZKPs. These are much easier to implement in ZKPs, and can be 100 or more times more efficient, but they come with other trade-offs. ↩

-

Mina allows for succinct verification of the whole chain, whereas Aleo focuses more on privacy. Also see Mina and Aleo. ↩

-

In Dark Forest, some people write very complex bots that play the game on its own. They even form private DAOs and create smart contracts that play the game semi-autonomously. ↩

-

Succinct Labs made Telepathy is one such project. zkBridge is another. There are likely many others. ↩

-

A weird, but surprisingly accurate, statement. ↩

-

Proof Carrying Data by 0xPARC, is one such example. See PCD. Also see Sismo. ↩

-

We won't go into these here, but I encourage the curious reader to search the web to find out how various projects are using or thinking about using ZKPs to achieve their design goals. Example: Unirep, Interep, RLN, RLNP2P, MACI, Filecoin, Stealthdrop, ETHDos, and many more. ↩

-

LLVM and WASM are compiler and toolchain technologies. Very roughly speaking, they allow you to write code in different programming languages that run in different types of environments, such as in different web browsers and on different types of computers. Understanding the specifics of these systems isn't important for our purposes, just that they allow us to write and use programs in many different environments. See LLVM, WASM. ↩

-

See Delphinus Labs, RISC Zero, Orochi Network, nil.foundation. ↩

-

See zk-MNIST and EZKL. There are also projects doing things like neural networks in more modern efficient proof systems like Nova. ↩

-

See article on fighting disinformation with ZK. ↩

-

See this essay by ludens at 0xPARC for more details on this idea. ↩

-

See TLS Notary ↩

-

See article (archive) ↩

-

Unlike Zero Knowledge Proofs, which allow you to make statements about private data, Multi-Party Computation (MPC) generalizes this concept and allows us to do computation on shared secrets. That is, if Alice and Bob have their own secret, we can write a program that combines these two secrets in some non-trivial way, without revealing anyone's secrets. This is what we want in a negotiation setting, because we want to compare stakeholder's private information in some way to reach an acceptable compromise. Most MPCs that exist today are quite limited and inefficient, but it is an exciting area of research with a lot of potential. ↩

-

A familiar story: see Sears vs Amazon. ↩

-

Quote from a panel at Devcon5. ↩