- Published on

Programming ZKPs: From Zero to Hero

A tutorial introduction for the working programmer.

Do you know why zebras have stripes? One theory is that it is a form of camouflage. When zebras are in a herd together, it makes it harder for the lion to distinguish their prey. Lions have to isolate their prey from the flock to be able to go after it. 1

Humans like to hide in a crowd too. One specific example of this is when multiple people act as one under a collective name. This was done for the Federalist Papers which led to the ratification of the United States Constitution. Multiple individuals wrote essays under the single Pseudonym "Publius". 2 Another example is Bourbaki, a collective pseudonym for a group of French mathematicians in the 1930s. This lead to a complete re-write of large parts of modern mathematics with their focus on rigor and the axiomatic method. 3

Bourbaki congress in 1938

In the digital age, let's say you are in a group chat and want to send a controversial message. You want to prove that you are one of its members, without revealing which one. How can we do this in the digital realm using cryptography? We can use something called group signatures.

Traditionally speaking, group signatures are quite mathematically involved and hard to implement. However, with Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), this math problem becomes a straightforward programming task. By the end of this article, you'll be able to program group signatures yourself.

Introduction

This post will show you how to write basic Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) from scratch.

When learning a new tech stack, we want to get a hang of the edit-build-run cycle as soon as possible. Only then can we start to learn from our own experience.

We will start by getting you to setup your environment, write a simple program, perform a so-called trusted setup, and then generate and verify proofs as quickly as possible. After that, we'll identify some ways to improve our program, implement these improvements and test them. Along the way, we'll build up a better mental model of the pieces involved in programming ZKPs in practice. At the end of, you'll be familiar with (one way of) writing ZKPs from scratch.

We will build up step by step to a simple signature scheme where you can prove that you sent a specific message. You'll be able to understand what this piece of code is doing and why:

template SignMessage () {

signal input identity_secret;

signal input identity_commitment;

signal input message;

signal output signature;

component identityHasher = Poseidon(1);

identityHasher.inputs[0] <== identity_secret;

identity_commitment === identityHasher.out;

component signatureHasher = Poseidon(2);

signatureHasher.inputs[0] <== identity_secret;

signatureHasher.inputs[1] <== message;

signature <== signatureHasher.out;

}

component main {public [identity_commitment, message]} = SignMessage();

You'll also have been given all the tools and techniques necessary to modify this to support the group signature scheme mentioned above.

Pre-requisites

We assume you are a software engineer with working experience in more than one programming language, who has basic familiar with using Unix-style command line interfaces. We also assume you have a passing familiarity with concepts like digital signatures, public-key cryptography and hash functions. Nonetheless, we'll introduce their relevant properties as they become relevant.

When it comes to Zero Knowledge Proofs, we assume you've read my previous post, A Friendly Introduction to Zero Knowledge. If you haven't read this article, we'll quickly recap the most important things here. For better understanding, we recommend reading the above article first. If you have already read it, you can safely skip the below.

Recap of ZKPs

Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) are a fairly new form of cryptography that have seen more practical applications lately. While traditional cryptography allows us to do things like signatures and encryption, ZKPs allows us to prove arbitrary statements in a general-purpose way.

Outside of proving arbitrary statements, ZKPs give us two key properties: privacy and compression. These are also known as zero knowledge and succinctness, respectively. Privacy means we can prove something without revealing anything else. Compression means the proof of an arbitrary statement stays roughly the same size regardless of how complex the computation we are proving is. ZKPs are also general-purpose. Roughly speaking, this is the difference between a calculator, made for a specific task, and a computer, that can compute anything.

Two concrete examples of ZKPs:

- We can take a digital identity card and prove that we are over 18 years old

- Without revealing anything else, like your full name or address

- We can prove that all state transitions have been executed correctly

- Such as in a public blockchain, with the resulting proof being very small

We can program many common types of ZKPs by writing special programs known as circuits. This allows one party, a prover, to create a proof of some statement. Another party, known as a verifier, can then verify this proof. Like a normal program, this program can take input and produce output. For these special programs, we can specify if the input is private or public. If it is private, it means only the prover can see this input. We program circuits by specifying constraints. One example of a constraint is "in a Sudoku puzzle all numbers 1 through 9 must be used exactly once in a row".

ZKPs are fairly new but they are already used a lot in public blockchains, for example, to allow private payments with fungible money, or to allow more transactions to be processed faster.

More and more applications are being discovered and developed every day. There are also a lot of different flavors of ZKPs, all with their own set of trade-offs, and it is a very active area of research. These different flavors are being developed rapidly, and allow for increased efficiency and other affordances.

Overview

We are going to use Circom and Groth16. Circom is a domain-specific language (DSL) for writing ZKP circuits. Groth16 is a common and popular proving system. Roughly speaking, a proving system is just one way that you can program ZKPs. Other DSLs and proving systems also exists.

We'll start by installing some tools and dependencies. After that, we'll proceed in the following rough steps:

- Write (write circuit)

- Build (build circuit)

- Setup (trusted setup)

- Prove (generate proof)

- Verify (verify proof)

After having gone through this flow once, we'll look at some problems with the current approach. We'll then make several incremental improvements, building up to the signature scheme above. Along the way, we'll explain necessary concepts and syntax.

At the end of each section, we'll also include some simple exercises that will check your understanding. These exercises are recommended. At the very end of the article we'll also include a list of problems. Problems are optional and require a lot more effort.

Preparation

First up, we have to install some tools and dependencies. We have prepared a git repo that makes it easier for you to get started without getting lost in the weeds with details. If you prefer not to install any software, see the end of this section.

The pre-requisites we require are:

rust(the programming language)just(a modernmake)npm(package manager for JavaScript)

The ZKP tools we will actually use are:

circom(for building our special program, or circuit)snarkjs(for setup, and generating/verifying proofs)justtasks (to simplify common operations related to above)

To install the above as well as make building and running things easier you can clone and use the git repo. This should work on any Unix-like system like MacOS and Linux. If you use Windows we suggest using a Linux VM, Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), or similar for development.

# Clone the repo and run the prepare script

git clone git@github.com:oskarth/zkintro-tutorial.git

cd zkintro-tutorial

# Skim the contents of this file before executing it

less ./scripts/prepare.sh

./scripts/prepare.sh

We recommend you skim the contents of ./scripts/prepare.sh to see what this will install, or if you prefer to install things manually. Once executed you should see Installation complete and no errors.

If you get stuck, please see the latest official documentation here. Once done, you should have the following versions (or higher) installed:

> circom --version

circom compiler 2.1.8

> snarkjs | head -n 1

snarkjs@0.7.4

In the repo there is a justfile that defines a set of common commands. These just commands aim to simplify common operations on ZKPs, so you can focus on conceptual understanding of the actual steps involved. This makes the process much less error-prone when you are starting out.

If at any time you want to see in more detail what commands are being executed, we recommend you look at the justfile and the various scripts in the scripts folder.

We highly recommend installing the above software for following along the tutorial and building intuition. However, If you do not want to install any software, you can follow along in a limited capacity using an online REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) tool such zkrepl.dev. If you do not want to install just and prefer to execute all the commands yourself you can do so with a little extra effort by using the accompanying shell scripts.

First iteration

We are now ready to start coding. To build up to the signature scheme mentioned above, we will start with a very simple program, the equivalent of a "Hello World" in other programming languages.

In practical terms, we will write a special program that will help us prove knowledge of two secret numbers whose product is a public number, without ever revealing the secret numbers themselves. For example, the public number might be "33" and the secret numbers are "11" and "3". This is an important stepping stone towards digital signatures and will build help intuition for how ZKPs work. If you are familiar with public-key cryptography, you can - very loosely - think of the secret numbers as a "private key" and the public number as a "public key".

Since this is a different way of programming involving many new concepts, don't worry if things don't make sense at first. You can always keep going, focusing on the code, generating proofs, etc and come back to a specific section later on.

Write a special program

Unlike most other programming, writing these special programs, circuits, look a bit different. What we are interested in is proving a set of constraints. 4 The simplest set of constraints we can prove consists of a single constraint. 5 What we will constrain is that two numbers multiplied by each other equal a third one.

Go to the example1 folder in the zkintro-tutorial repository above. There's a skeleton program in example1.circom. Modify it to look like this:

pragma circom 2.0.0;

template Multiplier2 () {

signal input a;

signal input b;

signal output c;

c <== a * b;

}

component main = Multiplier2();

This is our special program, or circuit. 6 Going line by line:

pragma circom 2.0.0;- defines the version of Circom being usedtemplate Multiplier()- templates are the equivalent to objects in most programming languages, a common form of abstractionsignal input a;- our first input,a; inputs are private by defaultsignal input b;- our second input,b; also private by defaultsignal output c;- our output,c; outputs are always publicc <== a * b;- this does two things: assigns the signalca value and constrainscto be equal to the product ofaandbcomponent main = Multiplier2()- instantiates our main component

The most important line is c <== a * b;. This is where we actually declare our constraint. This expression is actually a combination of two: <-- (assignment) and === (equality constraint). 7 A constraint in Circom can only use operations involving constants, addition or multiplication. It enforces that both sides of the equation must be equal. 8

On constraints

How do constraints work? In the context of something like Sudoku, we might say a constraint is "a number between 1 and 9". In the context of Circom however, this is not a single constraint, but instead something we have to express using a set of simpler equality constraints (===). 9

Why is this the case? This has to do with what is mathematically going on under the hood. Fundamentally, most ZKPs use arithmetic circuits which represents computation over polynomials. When dealing with polynomials, you can easily introduce constants, add them together, multiply them and check if they are equal to each other. 10 Other operations have to be expressed in terms of these fundamental operations. You do not have to understand this in detail in order to write ZKPs, but it can be useful to have some intuitition of what is going on under the hood. 11

We can visualize the circuit as follows:

Building our circuit

For your reference, the final file can be found in example1-solution.circom. For more details on the syntax, see the official documentation.

We can compile our circuit by running:

just build example1

This is a thin wrapper for calling circom to create a example1.r1cs and example1.wasm file. You should see something like:

template instances: 1

non-linear constraints: 1

linear constraints: 0

public inputs: 0

private inputs: 2

public outputs: 1

wires: 4

labels: 4

Written successfully: example/target/example1.r1cs

Written successfully: example/target/example1_js/example1.wasm

In this case, we have the following:

- two private inputs,

aandb - one public output,

c - one (non-linear) constraint,

c <== a * b

We will ignore other parts of the output above for now. 12 Now we have two files: example1.r1cs and example1.wasm.

r1cs stands for Rank 1 Constraint System. This file contains our circuit in binary form. and corresponds to how we define our constraints mathematically. 13

The .wasm file contains WebAssembly, which is what we need to generate our witness. The witness is how we specify the inputs that we want to keep private while still using them to create a proof.

We are not quite ready to make proofs yet though. First we need to perform a setup to get our prover and verification key.

Don't worry if it all doesn't make sense yet. It is a new way of doing things and it takes a while to get used to.

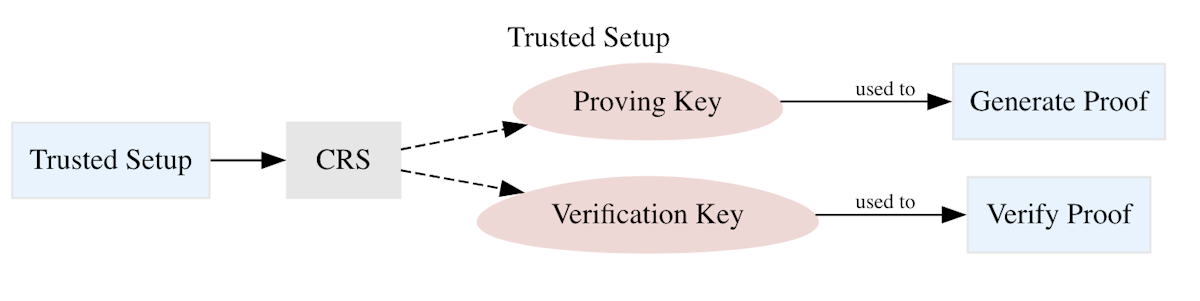

Trusted setup

With the artifacts we generated above, we can perform a trusted setup.

A trusted setup is something we run once as a pre-processing step. This generates what is called a Common Reference String (CRS), which consists of a proving key and a verification key. These keys can then be used every time we want to generate and verify proofs, respectively.

Why do we need these keys and who should have access to them? The prover key embeds all the information necessary to be able to generate a proof in a zero-knowledge preserving fashion for that specific circuit. Similarly, the verifier key embeds all the information necessary to verify that the proof is indeed correct. These aren't private keys, but instead information that can and should be publicly distributed. Any party that needs to generate or verify a proof should have access to them. 14

Why do we call it a trusted setup? Performing a setup is a process that involves multiple participants and it is sometimes called a ceremony. 15 All participants cooperate to create a cryptographic "secret", and this is the basis of how the proving and verification keys are constructed. If this process is manipulated, cryptographically it may be possible to create false proofs or falsely claim invalid proofs as verified. Hence, there's an assumption of trust that least some participants are honest in the setup process, giving rise to the term "trusted setup".

As a starting point, we are going to run the trusted setup ourselves. Run the following:

just trusted_setup example1

You'll be asked to supply some random text or entropy twice. 16 Once completed you should see "Trusted setup completed." and the location of the keys. The file ending in .zkey is our proving key. While going into the details of trusted setups is outside of the scope of this article, there are a few things that are useful to be aware of.

First, what is the problem with the above approach? Since we have just one participant, everyone else who is using the cryptographic key material from that setup is trusting that individual and their computer environment. This wouldn't work in a production scenarios where we'd want to maximize the number of participants to make the setup more trustworthy. If we have 100 people who participate, because of how this cryptographic secret is constructed, it is enough if one single individual is honest. 17

It is also worth knowing that different ZKP systems have different properties in terms of security, performance and affordances. While all ZKP systems require some form of setup, not all of them require a trusted setup. Of those that do, some differ in their requirements.

With Circom we are using the Groth16 proof system which does requires a trusted setup. Specifically, the setup is split into two phases: phase 1 and phase 2. Phase 1 is independent of a circuit and can be used by any ZKP program up to a certain size, whereas phase 2 is circuit-specific. When we ran the above command, we performed both phases.

You might be wondering, why would you use a trusted setup at all if you can avoid it? A lot of people agree with this view. However, there are still good reasons people use these systems - such as more mature tooling and ecosystem, as well as cheap verification costs. Cheap verification costs is something that is traditionally very important, especially when we are verifying proofs on a public blockchain like Ethereum. Depending on your use case, your choice will likely differ. In a different article we'll look more into trusted setups and their trade-offs, as well as different proof systems.

Generate proof

With the trusted setup completed above, we have a proving key and verification key. We can now generate a proof that we know two secret values whose product is another public number.

Specifically, let's prove that we know that 33 can be constructed from multiplying the numbers 3 and 11. Recall that our private input consists of signals a and b. We specify this in the example1/input.json file as follows:

{

"a": "3",

"b": "11"

}

That is, we specify the input as a JSON map, where the key is the signal name and the value is the value we want to assign it. Notice that the value is a string, even though it is conceptually a number. This is a quirk in Circom and its JS API. Due to the nature of ZKPs, we often deal with very large numbers that require the use of BigInt. The easiest way to specify such a large number in a JSON file is as a string that will then be converted to a BigInt.

We can create a proof using our compiled circuit (in WASM form), our proving key and the input by running the following:

just generate_proof example1

Under the hood, this command takes the input and generates a witness for our specific circuit. 18 Normally, by witness, we simply mean the private input we use to generate a proof. In the context of Circom, a witness is the complete assignment of all signals, both private and public, in a form that the prover software can process. This form is an internal representation in a binary format. 19

With this generated witness, we can create a proof using snarkjs. Finally, we end up with a proof and some public output.

The proof looks something like this:

{

"pi_a": ["15932[...]3948", "66284[...]7222", "1"],

"pi_b": [

["17667[...]0525", "13094[...]1600"],

["12020[...]5738", "10182[...]7650"],

["1", "0"]

],

"pi_c": ["18501[...]3969", "13175[...]3552", "1"],

"protocol": "groth16",

"curve": "bn128"

}

This specifies the proof in the form of some mathematical objects (three elliptic curve elements), pi_a, pi_b, and pi_c. 20 It also includes some metadata about the protocol (groth16) and the curve (bn128, a mathematical implementation detail we'll ignore for now) used. This allows the verifier to know what to do with this proof to verify it correctly.

Notice how short the proof is; regardless of how complex our special program is it'll only be this size. This showcases the succinctness property of ZKPs we talked about in our friendly introduction.

The command above also outputs our public output:

["33"]

This is a list of all the public outputs corresponding to our witness and circuit. In this case, there's a single public output that corresponds toc: 33. 21

What have we proven? That we know two secret values, a and b, whose product is 33. This showcases the privacy property we talked about in the previous article.

Note that the proof isn't useful in isolation, it requires the public output that comes with it.

Verify proof

Next up, let's verify this proof. Run:

just verify_proof example1

This takes the verification key, the public output, and the proof. With this we are able to verify the proof. It should print "Proof verified". Notice how the verifier is never exposed to any of the private inputs.

What happens if we change the output? Open example1/target/public.json and change the 33 to 34, then run the command above again.

You'll notice that the proof is not verified anymore. This is because our proof does not prove that we have two numbers whose product is 34.

Congratulations, you've now written your first ZKP program, performed a trusted setup, generated a proof and finally verified it!

Exercises

- What are the two key properties of ZKPs and what do they mean?

- What is the role of a prover and what input does she need? What about a verifier?

- Explain what the line

c <== a * b;does. - Why do we need to perform a trusted setup? How do we use its artifacts?

- Code: Finish

example1until you generated and verified a proof.

Second iteration

With the above circuit, we are proving that we know the product of two (secret) numbers. This is closely related to the problem of prime factorization, which is the basis of a lot of cryptography. 22 The idea is that if you have a very large number, it is hard to find two prime numbers whose product is that large number. On the flip side, it is very easy to check if the product of two numbers is equal to another number 23.

However, there is a big problem with our circuit. Can you see it?

We can easily change our input to be "1" and "33". That is, a number c is always the product of 1 and c. That's not very impressive at all is it?

What we want to do is to add another constraint, that neither a or b can be equal to 1. That way, we are forced to do proper integer factorization.

How can we add this constraint and what changes do we need to make?

Updating our circuit

We are going to work with the example2 folder for these changes. Unfortunately, we can't just write a !== 1, because this isn't a valid constraint. 24 It isn't made up of only constants, addition, multiplication and equality checks. How do we express that "something is not"?

This is not immediately intuitive, and this type of problem is where a lot of the art of writing circuits come into play. Developing this skill takes time and is outside of the scope of this initial tutorial; fortunately there are many good resources for this. 25

There are some common idioms though. The basic idea is to use a IsZero() template that checks if an expression is equal to zero or not. It outputs 1 for true, and 0 for false.

It is often helpful to use a truth table 26 to show possible values. Here's the truth table for IsZero():

| in | out |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| n | 0 |

This is such a useful building block that it is included in Circom's library, circomlib. In circomlib there are also many other useful components. 27

We can include this by creating an npm project (JavaScript) and adding it as a dependency. In the example2 folder we have already done this for you. To import the relevant module, we add the following line to the top of example2.circom:

include "circomlib/circuits/comparators.circom";

Using IsZero(), we can check if either a or b is equal to 1. Modify the example2.circom file to contain the following lines:

component isZeroCheck = IsZero();

isZeroCheck.in <== (a - 1) * (b - 1);

isZeroCheck.out === 0;

In the above code snippet, we create a new component isZeroCheck, instantiating the IsZero() template. If either a or b is equal to 1, isZeroCheck.in will be assigned 0, and isZeroCheck.out will be 1. Since we have a constraint that says isZeroCheck.out === 0, this constraint will fail. This means that we can no longer provide inputs where either a or b is equal to 1.

I encourage you to convince yourself, either in your head or using pen and paper (perhaps using a truth table?), that this is true. If you are up for a challenge, you can try to figure out how IsZero() is implemented. it is only a few lines of code. You can see the code in circomlib's comparators.circom file. 28

For your reference, the final file can be found in example2-solution.circom. With the changes above, we can install the npm circomlib dependency and build our circuit with:

just build example2

Re-running our trusted setup

With Circom and Groth16, any time we change our circuit we have to re-run our trusted setup. This means you better be sure your circuit is solid before you release it. Especially if you are running a proper ceremony involving many participants.

More specifically, we only have to run the circuit-specific (phase 2) trusted setup again. This is because phase 1 is generic for any Groth16 circuit written in Circom, up to a certain size. When we performed the trusted setup above, we did both phase 1 and phase 2, but omitted the details of phase 1 for simplicity. Here are some more details on phase 1 to give a more complete picture.

The result of the phase 1 trusted setup is kept in a .ptau file, where ptau stands for powers of tau. 29 Mathematically, this file contains powers of some random secrets. This is what allows us to "accommodate" some number of number of constraints. We don't need to understand how this works mathematically, but there are two key facts that are useful to know: (a) .ptau is circuit-independent (b) the size of it indicates its capacity. The "capacity" of a given ptau is 2^n - 1 constraints, where n is some number. For example, pot12.ptau indicates that the number of constraints it can accommodate is 2^12 - 1, or slighty over 4000 constraints.

Since we don't want to re-run our phase 1 again, we just want to run phase 2. This will use the previously generated pot12.ptau (stored in the ptau directory) as input. We can run our phase 2 trusted setup with:

just trusted_setup_phase2 example2

Testing our changes

With this, we can run:

just generate_proof example2

just verify_proof example2

It still generates and verifies the proof as expected.

If we change the example2/input.json inputs to say 1 and 33 and try to run above we will see an assert error. That is, Circom won't even let us generate a proof, because the input is breaking our constraints.

Complete flow diagram

Now that we have gone through the entire flow twice, let's take a step back and see how all of the pieces fit together.

Hopefully things are starting to make some sense. With that, let's kick it up a notch and make our circuit more useful.

Exercises

- Why do we have to run phase 2 but not phase 1 of our trusted setup for

example2? - What was the main problem with the previous example and how did we fix it?

- Code: Finish

example2until you failed to generate a proof.

Third iteration

With the above circuit we have proven that we know the product of two secret values. That on its own is not very useful. Something that is useful in the real world is a digital signature scheme. With it, you can prove to someone else that you wrote a specific message. How would we go about implementing this using ZKPs? To get there, we must first cover some basic concepts.

Now would be a good time for a short break to get a fresh cup of your favorite beverage.

Digital signatures

Digital signatures exists already and are everywhere in our digital age. The modern Internet wouldn't function without them. Usually, these are implemented using public-key cryptography. In public-key cryptography you have a private key and a public key. The private key is for your eyes only, and the public key is shared publicly, representing your identity.

A digital signature scheme consist of the following parts:

- Key generation: Generate a private key and a corresponding public key

- Signing: Create a signature using the private key and the message

- Signature verification: Verify message was signed by corresponding public key

While the specifics look different, the program we wrote and the key generation algorithm above share a common element: they both use a one-way function, and more specifically a trapdoor function. A trapdoor is something that is easy to fall into and hard to climb out of (unless you can find a hidden ladder). 30

For public-key cryptography, it is easy to construct the public key from the private key, but very hard to go the other way. The same is true for our previous program. If the two secret numbers are very large prime numbers, it is very hard to turn that product back into the original values. Modern public-key cryptography often uses elliptic curve cryptography under the hood.

Traditionally, creating cryptographic protocols like these digital signature schemes is a lot of hard work and requires coming up with a specific protocol that involves using some clever math. We don't want to do that. Instead, we want to write a program using ZKPs that achieves the same result.

Instead of this: 31

We just want to write a program, generate a proof of what we want, and then verify this proof.

Hash functions and commitments

Instead of using elliptic curve cryptography, we are going to use two much simpler tools: hash functions and commitments.

A hash function is also a one-way function. For example, on the command line we can use the SHA-256 hash function like this:

echo -n "foo" | shasum -a 256

To produce the hash of "foo": 0beec7[...]a8a33 (abbreviated). 32

On its own, a hash function is not a trapdoor function. There's no special knowledge that allows us to retrieve the original value. It acts more as a meat grinder and less as a trapdoor with a hidden ladder.

What about commitments? A commitment is simply a way to commit ("to promise") to a secret value so we can't change our mind about it later. In our case, we will use a commitment to generate the equivalent of a public key using some secret value. We can do this using a hash function.

Commitment schemes are a very common cryptographic primitive. 33 They allow us to:

- commit: Commit to a specific value while keeping it hidden

- reveal: Reveal this value so it can be verified to be correct

This gives us two key properties:

- hiding: the value stays hidden

- binding: you can't change your mind about the value

One way to think about a commitment is to imagine giving a lock box to a friend. You can't change the contents of the box after the fact, but your friend can't look inside it. Only when you give them the key can they open it.

Going back to our digital signature scheme, we have:

- Key generation: Create some secret string and hash it to create a commitment

- Signing: Create a signature by hashing the secret together with the message

- Verification: Verify proof using commitment, message and signature (public output)

In pseudo-code this is what we want to do in our circuit:

commitment = hash(some_secret)

signature = hash(some_secret, message)

At this point you probably have some questions. Let's address a few likely questions you have in your mind.

First of all, why does this work and why do we need a ZKP for this? When someone is verifying the proof, they only have access to the commitment, message, and signature. There's no direct way to verify that the commitment corresponds to the secret, without revealing the secret. In this case, we are just "revealing" the secret when generating our proof, so our secret stays safe.

Second, why use these hash functions and commitments instead of public key cryptography inside the ZKP? You absolutely could do public key cryptography inside a ZKP, and there are valid reasons to do so. It is a lot more costly to implement in terms of constraints than the above. This makes it a lot slower than the above, simpler scheme. As we'll see in the next section, the choice of hash function turns out to very important.

Finally, why use a ZKP at all when we already have public key cryptography? In this simple example, there's no need for a ZKP. However, it acts as a building block for more interesting applications, such as the group signature example mentioned in the beginning of this article. After all, we want to program cryptography.

That was a lot! Luckily, we are over the hump now. Let's get coding. Don't worry if not all of the above made complete sense to you at first. It takes a while to get used to this type of reasoning.

Back to the code

We are going to work from the example3 directory.

To implement digital signatures, the first thing we need to do is to generate our keys. These correspond to the private and public key in public-key cryptography. Because the keys correspond to an identity (you, the prover), we will call these identity_secret and identity_commitment, respectively. Together they form an identity pair.

These will be used as input to the circuit, together with the message we are signing. As public output, we'll have the signature, commitment and message. This will allow someone to verify that the signature is indeed correct.

Because we need the identity pair as input to the circuit, we generate these separately:

just generate_identity

This produces something like this:

identity_secret: 43047[...]2270

identity_commitment: 21618[...]0684

In order to keep the secret secure, we use a big and random number. Unlike what we saw before, we are not using a hash function such as SHA-256 to create the commitment. Instead, we are using what is called a ZK-Friendly hash function. That is a special hash function that is optimzed for being used in ZKPs. This matters a lot in terms of performance when you do a lot hashing. The ZK friendly hash function we are using is called the Poseidon hash function. 34

Under the hood, this is using the circomlibjs library to wrap circomlib. This is a JavaScript library that allows us to use Circom circuits. This ensures our identity_commitment is generated in exactly the same way in JavaScript/on the command line as in our circuit. If you want to read the script source code it is available in example3/generate_identity.js.

Just like we did before with IsZero, we need to include the Poseidon template. We do this with the following include:

include "circomlib/circuits/poseidon.circom";

The Poseidon hash template is used as follows:

component hasher = Poseidon(2);

hasher.inputs[0] = foo;

hasher.inputs[1] = bar;

quux <== hasher.out

We specify that the hasher component expects two arguments, specified in the .inputs[] array. It then assigns the output signal to .out. In this example, it takes foo and bar as inputs, hashes them together and the result is quux. 35

Finally, we introduce a new piece of syntax:

component main {public [identity_commitment, message]} = SignMessage();

By default, all inputs to our circuit are private. With this, we explicitly mark identity_commitment and message as public. This means they'll be part of the public output.

With this information you should have enough to complete the example3.circom circuit. If you are still stuck, you can refer to example3-solution.circom for the full code.

Like before, we have to build the circuit and run phase 2 of the trusted setup:

just build example3

just trusted_setup_phase2 example3

When building the circuit, you might notice how the number of constraints went up quite a lot compared to example2. This is primarily due to the use of two Poseidon hashes. 36

Testing our circuit

For reference, here's an illustration of our completed circuit:

We can now generate a proof. We have the following input in example3/input.json:

{

"identity_secret": "21879[...]1709",

"identity_commitment": "48269[...]7915",

"message": "42"

}

Feel free to change the identity pair to the one you generated yourself with just generate_identity. After all, you want to keep the identity secret to yourself!

You might notice how the message is just a number quoted as a string ("42"). Unfortunately, because of how constraints work mathematically (using linear algebra and arithmetic circuits) we can only use numbers and not strings. The only operations that are supported inside of circuits are basic arithmetic ones like addition and multiplication. 37

We can now generate and verify a proof:

just generate_proof example3

just verify_proof example3

As before, the proof stays the same size, even though we are doing a lot more things. The public output found in example3/target/public.json is:

["48968[...]5499", "48269[...]7915", "42"]

This corresponds to the signature, commitment, and message respectively.

Let's look at how things can go wrong if we are not careful. 38

First, what happens if we change the identity commitment to something random in the input.json? You'll notice we can't generate proofs anymore. This is because we are also checking the identity commitment inside the circuit itself. It is critical that this relationship between the identity secret and commitment is maintained.

Second, what happens if we don't include the message in the output? We do get a proof and it gets verified. But the message could be anything, so it doesn't actually prove that the you sent a specific message. Similary, what if we don't include the identity commitment in the public output? This means that the identity commitment could be anything, so we don't actually know who signed the message.

As a thought exercise, convince yourself (or try out) what could go wrong if we omit either of these two key constraints:

identity_commitment === identityHasher.outsignature <== signatureHasher.out

Congratulations, you now know how to program cryptography! 39

Exercises

- What are the three components of a digital signature scheme?

- What is the purpose of using a "ZK-Friendly hash function" like Poseidon?

- What are commitments? How can we use them for a digital signature scheme?

- Why do we mark the identity commitment and message as public?

- Why do we need the identity commitment and signature constraints?

- Code: Finish

example3until you generated and verified a proof.

Next steps

With the above digital signature scheme, and some tricks we saw earlier in the article, you have all the tools at your disposal to implement the group signature scheme mentioned at the start of the article. 40

Skeleton code exists in example4. All you need is 5-10 lines of code. The only new syntax is a for loop, which works just as in most other language. 41.

This circuit will allow you to:

- sign a message

- proving that you are one of three people (identity commitments)

- but not reveal which one

You can think of it as a puzzle. The key insight essentially boils down to a single arithmetic expression. Try to work it out on paper if you can. If you get stuck, you can check the solution as before.

Finally, if you want some extra challenges, here are some ways to extend it:

- Allow arbitrary many people in the group

- Implement a new circuit

revealthat proves you signed a specific message - Implement a new circuit

denythat proves you did not sign a specific message

Creating a cryptographic protocol like this using classical tools would be a huge task requiring a lot of specialized knowledge. 42 With ZKPs you can become productive and dangerous in an afternoon, treating these problems as programming tasks. And this is just the tip of the iceberg of what we can do.

Exercises

- What do group signatures do over normal signatures? How can they be used?

Problems

These problems are optional and require a lot more effort.

- Figure out how

IsZero()is implemented. - Code: Finish the group signature scheme above (see

example4). - Code: Extend the group signature example above: Allow for more people and implement

revealand/ordenycircuits. - How would you design a "ZK Identity" system for proving you are over 18? What are some other properties you might want to prove? At a high level, how would you implement it, and what challenges do you see? Research existing solutions to get a better understanding of how they are implemented.

- For public blockchains like Ethereum, sometimes a Layer 2 (L2) is used to allow for faster, cheaper and more transactions. At a high level, how would you design an L2 using ZKPs? Explain some challenges you see with this. Research existing solutions to get a better understanding of how they are implemented.

Conclusion

In this tutorial introduction, we've gotten familiar with how to write and modify basic ZKPs from scratch. We setup our programming environment and wrote a basic circuit. We then performed a trusted setup, created and verified proofs. We identified some problems and improved our circuit, making sure to test our changes. After that, we implemented a basic digital signature scheme using hash functions and commitments.

We also learned enough skills and tools to be able to implement group signatures, something that would be difficult to implement without ZKPs.

I hope you have developed a better mental model of what is involved in writing ZKPs, and have a better sense of what the edit-run-debug cycle looks like in practice. This will work as a good foundation for any other ZKPs program you may write in the future, regardless of what tech stack you end up using.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Hanno Cornelius, Marc Köhlbrugge, Michelle Lai, lenilsonjr, and Chih-Cheng Liang for reading drafts and providing feedback on this.

Images

- Bourbaki Congress 1938 - Unknown, Public domain, via Wikimedia

- Hartmann's Zebras - J. Huber, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia

- Trapdoor Spider - P.S. Foresman, Public domain, via Wikimedia

- Kingsley Lockbox - P.S. Foresman, Public domain, via Wikimedia

References

Footnotes

-

While illustrative as a metaphor, this is just one of several theories. If you are curious, check out https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zebra#Function. ↩

-

See Bourbaki (Wikipedia). ↩

-

Unless you have done some form of declarative programming (as in: non-procedural, like Prolog, this is probably new to you. To some extent we do this in SQL too. We describe what we want, not necessarily how we want it done. ↩

-

Technically, zero constraint is also a set of constraints. While said in jest, under-constrained circuits are a big problem that can lead to many serious bugs. We will see an example of this later on. ↩

-

We call it a circuit, or more precisely an arithmetic circuit, because it connects inputs and outputs in a similar fashion to logical gates such as NAND, AND, NOT, XOR, etc gates. From this we can build a universal computer, or universal circuit. ↩

-

In general, using

<--is not recommended and you should almost always avoid it by using<==instead. ↩ -

This makes writing constraints quite challenging, as you can imagine. See https://docs.circom.io/circom-language/constraint-generation/ for more details on constraints in Circom. ↩

-

To say "this number is between 1 and 9" we have to implement a range check. This includes decomposing the number into bits and performing equality checks on them them. Luckily, a lot of these types of constraints have already been written and be re-used, as we'll see later with circomlib. ↩

-

For example

p(x) = ax^2 + bx + ccan easily be added, multiplied together or compared withq(x) = dx^2 + 2bx + e. It is worth noting that in ZKPs we operate over finite fields, not real numbers. This is out of scope of this article, thoguh. ↩ -

While most ZKPs use arithmetic circuits, there are other proving systems work with other abstractions. For example, zkSTARKs and Bulletproofs. ↩

-

Linear constraint means it can be expressed as a linear combination using only addition. This is equivalent to using multiplications with constants. The main thing to be aware of is that linear constraints are less complex than non-linear ones. See constraint generation for more details. Wires and labels refers to what the arithmetic circuit looks like. This is not something you usually have to care about. See arithmetic circuits for more details. ↩

-

Mathematically, what we are doing is making sure the equation

Az * Bz = Czholds, whereZ=(W,x,1).A,B,andCare matrices,Wis the witness (private input), andxis public input/out. While useful to know, it is not necessary to understand this for writing circuits. See Rank-1 constraint system for more details. ↩ -

: A better, but less commonly used, term here would be "proving parameters" and "verification parameters", respectively. This would be a bit more intuitive as keys are usually meant to be private. We will keep using "key" as opposed to "parameter" because that is what you are most likely to run into in the wild. ↩

-

As mentioned in the friendly introduction article, there's a great layman's podcast on The Ceremony Zcash held in 2016 that you can listen to here. Since then, a lot has changed in terms of trusted setups, and they are much easier to run and participate in. ↩

-

This is because we rely on randomness to make the generation of proving and verification keys secure. In a real trusted setup, getting more sources of entropy is often desirable. ↩

-

We call this a 1-out-of N trust model. There are many other trust models; the one you are most familiar with is probably majority rule, where you trust the majority to make the right decision. This is basically how democracy and most voting works. ↩

-

Since we always generate the witness together with the proof, the resulting binary file

witness.wtnsis mostly an intermediate step and an implementation detail. We use it straight away to generate the proof, which is why it is omitted from the diagram. ↩ -

In the literature, a witness is just the

Wpart of the vectorZ=(W,x,1)used in R1CS, wherexis all the public/input signals. In Circom, the whole vector is referred to as the witness. Also see note 13. ↩ -

The numbers have been abbreviated for brevity with

[...]. Mathematically, these are elliptic curve points on the bn128 curve, with a field size of 254-bits. A 254-bit number can have up to 77 digits in its decimal representation. ↩ -

The output is a bit unintuitive in that it doesn't map to the original signal name like this:

{"c": "33"}. This requires the developer to re-map the outputs according to the order they were defined in the circuit. This is due to the implementation ofsnarkjswhere we lose the variable information for proof generation. ↩ -

Also known as a cryptographic hardness assumption. See Computational hardness assumption (Wikipedia). ↩

-

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integer_factorization for more. ↩

-

While we can add asserts, these aren't actually constraints but only used for sanitizing input. See https://docs.circom.io/circom-language/code-quality/code-assertion/ for how that works and https://www.chainsecurity.com/blog/circom-assertions-misconceptions-and-deceptions for an example of how misusing asserts can go wrong. For more intuition on what constraints are, see the previous section On constraints. ↩

-

This resource by 0xPARC is excellent if you want to dive deeper into the art of writing (Circom) circuits: https://learn.0xparc.org/materials/circom/learning-group-1/circom-1/ (in particular the Circom workshops). Reading the standard library can also be illuminating, see note 26. ↩

-

Due to the nature of writing constraints, this comes up a lot. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truth_table. ↩

-

See https://github.com/iden3/circomlib for more on circomlib. ↩

-

See https://github.com/iden3/circomlib/blob/master/circuits/comparators.circom. ↩

-

People usually share these

ptaufiles across projects for increased security. See https://github.com/privacy-scaling-explorations/perpetualpowersoftau for details. You can also find a list of these ptau files, of various size, in https://github.com/iden3/snarkjs. ↩ -

Here the ladder represents some value that allows us to go the opposite, "hard" way. Another way to think about it is as a padlock. You can easily lock it, but hard to unlock it, unless you have a key. Trapdoor functions also have a more formal definition, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapdoor_function. ↩

-

Screenshot from Wikipedia. See ECDSA (Wikipedia). ↩

-

This command should work on most Unix-style systems. We use

-nto specify no newline character (foo, notfoo\n), and-ato specify we want SHA256. ↩ -

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commitment_scheme. Note that we don't always need the "hidden" property. For example, when it comes to using ZKPs to make Ethereum more scalable, we only want an efficient subset reveal of the state trie. ↩

-

We use Poseidon, but there are many others. Why is it faster? These ZK-friendly hash functions are implemented using arithmetic operations on prime fields, not bitwise operations like SHA256. it takes a lot fewer constraints to implement, which results in faster proving time. The performance difference between the two can be up to two orders of magnitude. On the flip side, a hash function like SHA256 has been studied more rigorously than most of these new ZK-friendly hash functions. ↩

-

In ZKPs, we often want to hash multiple things together. Unlike a traditional context, we can't just concatenate strings together ("foo bar"), so we instead specify how many inputs we have to our hash function. ↩

-

As mentioned in the note above, if this was using SHA-256 or doing some elliptic curve math the constraint count would be a lot higher. If we had more than 4000 constraints, we'd have to perform (or re-use) another phase 1 trusted setup with a higher capacity ptau. ↩

-

We can however encode our string as a byte array, using Unicode or ASCII. In a real application you'd probably use the hash of your message in its BigInt representation instead. ↩

-

In a real-world digital signature scheme, where multiple messages are exchange, we'd also probably want to introduce a cryptographic nonce. This is to avoid replay attacks, where someone could re-use the same signature at a later time. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Replay_attack. ↩

-

For real-world applications, try to re-use existing work and best practices as much as possible. There are a lot of things that can go wrong if you aren't careful. Luckily, this is getting easier and easier as the ZKP ecosystem mature. At a certain stage, a lot of high-risk applications do security audits to make sure their applications are secure (or at least not provably insecure). ↩

-

Implementing group signatures in ZKP was inspired by 0xPARC, see https://0xparc.org/blog/zk-group-sigs. ↩

-

In comparison, a paper implementing group signatures like https://eprint.iacr.org/2015/043.pdf involves some heavy cryptography and math. ↩